Recent research by the Guardian has found that Cloud Service Provider (CSP) emissions are likely to be nearly eight times higher than publicly disclosed.

Carbon emissions from cloud computing are primarily generated through data center power consumption, or operational emissions. CSPs create operational emissions when they purchase electricity from fossil fuel sources, to power their data centers. Whilst CSPs have faced pressure in recent years to reduce their carbon emissions, demand for cloud services has increased. Subsequently, they have resorted to methods of carbon reporting that distribute responsibility away from their own operations. The two primary methods for this are the purchase of renewable energy certificates, and the use of third-party facilities.

As well as energy generation, CSPs also produce emissions in the form of embodied carbon: the emissions generated during the manufacture, transport, and disposal of cloud service hardware. This article focuses specifically on operational emissions; you can read more about embodied emissions in How Does Cloud Computing Create Emissions?.

CSPs don’t have to use the renewable energy they buy.

Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) prove that energy was generated from renewable sources. However, companies can buy RECs separately from the actual units of power. This means that whilst they fund the renewable energy supplier, there is no obligation to have to use that renewable energy to power their operations. RECs provide companies with green credentials when they can’t – or don’t want to – exchange their fossil fuel energy supply for a renewable one. CSPs are therefore heavily reliant on RECs to fulfil their renewable energy and net zero targets.

This has led to the development of two methods for measuring emissions: location-based and market-based. Market-based emissions include RECs and carbon offsetting certificates: rather than actual emissions, they represent the investment in the renewable energy market that a company has made. Location-based emissions exclude RECs and offsets, and therefore represent the actual emissions generated by the actual power consumption of an organization at that particular location. CSPs are not elusive about their use of RECs: AWS proudly announces in its Sustainability Reports and promotional materials that ‘100% of electricity consumed by Amazon was matched with renewable energy sources in 2023’.

CSPs outsource their emissions to third-party data centers.

It is also common for CSPs to rent data center facilities from third parties; on average, CSPs generate half of their computing capacity through third-party contracts. Because those third-party organizations pay for the electricity that powers the data centers, CSPs are under no obligation to report the resulting power consumption or emissions generation. This is because such emissions would not be considered Scope 2 (emissions resulting for the purchase of electricity) but Scope 3 (emissions resulting from an organization’s supply chain). Large organizations in most countries are now legally required to report their Scope 2 emissions, but not Scope 3. Third-party data center operators themselves can also decide how to categorize their own power consumption and emissions: some report them as Scope 2, whilst others consider the emissions to be the responsibility of the CSPs that rent from them and therefore class them as Scope 3.

AWS claimed to produce no carbon emissions in 2023. It actually generated 126,755 tons of CO2e.

Amazon’s use of RECs and third-party contracting allows it to publicly claim to have achieved the goals of its Carbon Reduction Plan, which began in 2020. In 2020, Amazon’s cloud service, AWS, reported 2,813 tCO2e. In 2023, their use of RECs and third-party contracting meant they could report 0 tCO2e.

The reality was that AWS’ self-reported location-based emission figures more than doubled in that period, from 61,346 to 126,755 tCO2e. This means that AWS is now using more than twice as much fossil fuel generated electricity than in 2020.

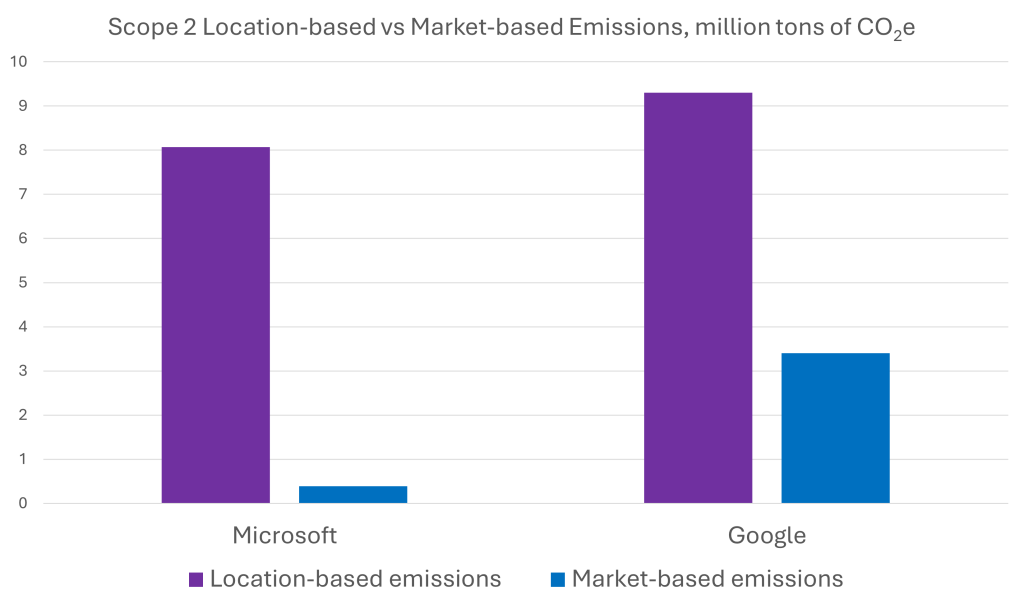

That gap between location-based and market-based emissions is replicated in other CSPs’ figures. Microsoft and Google do not report specifically on the emissions of their cloud services. Instead, the graph below shows the difference between the self-reported Scope 2 location-based and market-based emissions of all of Microsoft and Google’s operations – the main source of which is data centers, but which also includes office space.

Sources: Microsoft’s 2024 Environmental Sustainability Report Data Fact Sheet and Google’s 2024 Environmental Report. Amazon/AWS is not included in this graph because their data covers only their cloud service; Microsoft and Google’s data covers all aspects of their operations.

The future: more AI, more emissions, more regulation.

Despite growing awareness of the carbon impact of data centers, their electricity consumption is expected to increase by 600% over the next ten years (National Grid, 2024). This will be driven primarily by a rapid expansion in the use of AI. The processes required to deliver AI services are far more energy intensive than traditional computing and cloud services: one query to ChatGPT requires 10 times more electricity than a ‘traditional’ Google search query (IEA, 2024).

In response, governments and international bodies around the world are racing to implement carbon regulations that may curb the impact of increased computing power consumption. From 2025, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive will require organizations to report Scope 3 emissions, bringing cloud computing emissions in-scope for the first time. Countries in markets around the world, including the UK, Japan, Australia, China, Brazil, and Canada, are all developing their own mandatory Scope 3 reporting regimes. These regulations will put pressure on CSPs to report the full scope of their emissions. It will also require the users of their cloud services to take accountability for their contribution to those emissions.

How can Tailpipe help?

Tailpipe calculates the actual, location-based emissions of an organization’s use of CSP services. It does so by determining the power consumption of an organization’s cloud computing services, and factoring in the carbon intensity of the energy sources powering the data centers in which the organization’s cloud services are based. This generates an accurate, transparent, and comprehensive report into an organization’s Scope 3 cloud emissions. Tailpipe then recommends methods to reduce an organization’s cloud emissions, as well as cost-savings.

To find out more about how Tailpipe can help with your Scope 3 reporting requirements, operational carbon emissions, and cloud spend, get in touch with our team here.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Websites store cookies to enhance functionality and personalise your experience. You can manage your preferences, but blocking some cookies may impact site performance and services.

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Google reCAPTCHA helps protect websites from spam and abuse by verifying user interactions through challenges.

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us understand how visitors use our website.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool that tracks and analyzes website traffic for informed marketing decisions.

Service URL: policies.google.com (opens in a new window)

You can find more information in our Cookie Policy and Privacy Policy.